Eleanor Spencer @eleanor / February 11, 2021

Our oceans are changing rapidly due to human induced climate change, and not for the better. We can see these changes occurring with our own eyes but only on the ocean surface, through floating plastic, rising sea levels and washed up dead sea creatures entangled in ghost nets (i.e. discarded fishing nets).

But it is below the surface, in the murky shallows, that our eyes cannot see what is happening to our fragile coastal marine ecosystems. Scuba diving is one of the best ways to do this, but there are risks and costs associated with this practice.

This is why scientists like Scott Maharry, Senior Biologist at Grette Associates, are increasingly looking to ROVs to help them monitor how benthic (seabed) ecosystems are being affected by such changes.

Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs) can range from deep ocean surveyors equipped with a wide array of sampling equipment like temperature monitors and chemical samplers, to smaller shallow water observers which usually only have high definition cameras with lights installed, making them well-suited for coastal habitat surveying.

It is this type of smaller class ROV that Maharray used for his research into potential eelgrass restoration in the Port of Seattle. I spoke to him about his experience to get a better understanding of how ROVs are used by marine surveyors.

Looking at the world below

“What they [the Port of Seattle] wanted to know was the potential for eelgrass restoration and transplanting along the shoreline,” Scott Maharry said. “Rather than conducting a dive survey, which is what we typically do for eelgrass delinations or mapping a known area of eelgrass, I proposed using an ROV because we can survey a bigger area for less effort in terms of both cost and diver safety.”

For health and safety reasons, scuba divers are only permitted to stay submerged for a few minutes at a time. In fact, within a 3-hour shift, divers will only spend around 40 minutes under water. ROVs on the other hand, can stay down for hours at a time. Moreover, between divers’ remuneration and high equipment costs, scuba diving is not the most cost effective way of surveying benthic habitats.

Consequently, the cost and risk for divers to perform survey dives can prohibit environmental organizations - especially smaller ones with less access to funding - from conducting essential work on threatened coastal habitats.

When conducting any environmental survey, the location of each site needs to be logged so the exact same position can be surveyed in the future - i.e. quantitative data. This is usually done by scuba divers who dive down to mark the location, or installing additional location software to the ROV that then needs to be overlaid with the footage once back in the lab, which is a time consuming job.

“If we did want to georeference something then we would just dive and put buoys out and georeference it manually,” Maharry said.

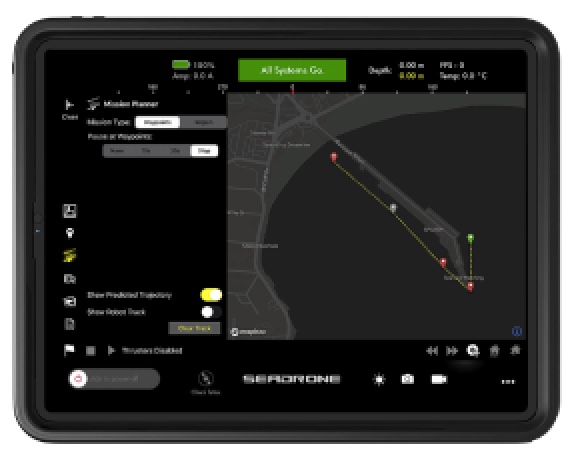

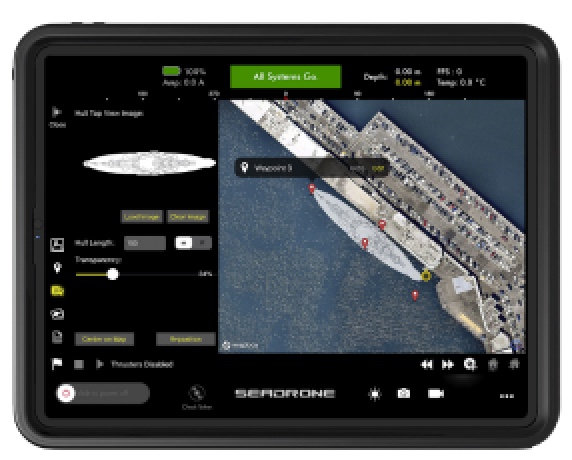

Few people know that the SeaDrone PRO Software can also accomplish this task. Even though this solution is optimized to expedite ship hull inspections, you can setup waypoints and tags georeferenced with respect to global coordinates in a matter of minutes using SeaDrone’s mission planner.

However, “the ROV meant we could get a qualitative look at the shoreline, meaning we were able to get eyes on the eelgrass and evaluate their condition to assess if they were good enough for transplanting. We can get a look at substrate condition and any other limiting factors that could preclude us from using these areas for transplant.”

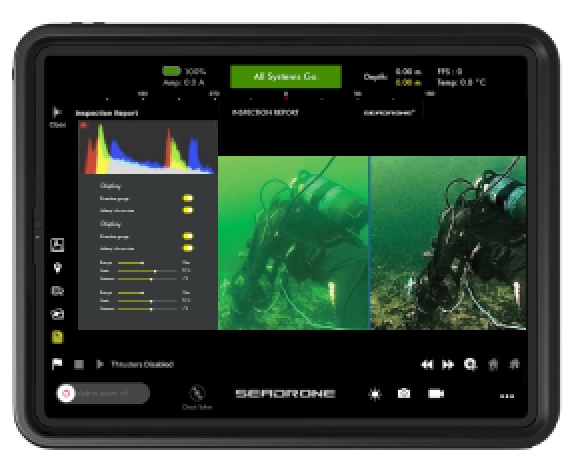

Smaller ROVs are better suited to surveying epifauna organisms (organisms that live on the surface on the seabed, e.g. oysters) than traditional techniques, since dredging or trawling can cause significant damage to these ecosystems. This is especially true when considering biogenic habitats (created by plants and animals) and fragile epifauna, such as corals and sponge rich habitats, where even being stepped on by a diver could cause irreversible damage to these fragile ecosystems. By contrast, an ROV equipped only with a camera has the ability to identify species without even disturbing them.

Sometimes you need more than eyes

But there is a downside to being non-invasive to an environment: it can limit a scientists ability to see what is within the seabed, like the sedimentary species. (Funny to think that not damaging an environment could be a bad thing!)

But a camera can only show you what is directly on the surface of the sediment; to see what is in the sediment, you need a dredge or a trawl to dig it out so it can be looked at in a lab later. More often than not, this does cause significant damage to sedimentary ecosystems. So if you would like to know what is going on above the surface of the seafloor, use an ROV; if you want to see below it then use a dredge.

There are other limitations as well when using ROVs in marine science.

On reflection, Maharry remarked: “the only thing we noticed was that the thrusters got quickly clogged with macroalgae and then it would float to the surface, but it was a quick fix once we knew what was going on. (...) The place we were working was a high current and high macroalgae region; we worked out some good fixes and it wasn’t a big issue. ”

Additionally, the tether that connects the ROV to the controller could also become an issue in areas with a high current. If it were to become tangled, then it could cause the marine surveyors to have to stop their work and recall the ROV to fix the issue. But this can easily be avoided with thorough planning, greater spatial awareness and deployment strategies.

Some people may be thinking, ‘but the whole reason for becoming a marine biologist is so you can get in the water and see for yourself what is there’. The truth is the vast majority of marine biologists don’t scuba dive and even for those that want to may not be able to due to pre-existing health conditions. ROVs provide a way for them to see the ocean's depths in all their glory.

This technology should not be seen as something that is taking away from marine scientists, but giving more to those who might not have considered this as a field before due to their own limitations.

Like Maharry said, “it adds another tool to the toolbox.”

Scott getting ready for a SeaDrone front loaded squat: Stand with feet wide, toes pointing forward, and hold a SeaDrone in front of you. Nevermind, Scott from Grette Associates is actually performing a full body workout, he is surveying a wild habitat on the northwestern coast of Washington.

“What they [the Port of Seattle] wanted to know was the potential for eelgrass restoration and transplanting along the shoreline”

Scott Maharry Inspecting - Squid Eggs

“Smaller ROVs are better suited to surveying epifauna organisms (organisms that live on the surface on the seabed, e.g. oysters) than traditional techniques”

“ROVs provide a way for them to see the ocean's depths in all their glory. ”

“It adds another tool to the toolbox.” - Scott Maharry